Gothic Library - Horace Walpole - Castle of Otranto - 1764

It's finally time! I'm rereading The Castle of Otranto for Christmas and you get the wonderful opportunity to follow along (without also having to read it)!

Why Christmas? The novel was actually first published on Christmas Eve 1764. It's the first "gothic" novel in the literal sense: the word just meant architectural style before Walpole added it to the second edition the following year.

So I called this the prefatory materials, not because I'm writing a preface to the series but because Walpole's prefaces are actually really important . The first one is in character. Walpole claims to be translating this book from the Italian. He even says that it was printed in a fine black letter script.

Which means it looks like this.

𝕸𝖆𝖓𝖋𝖗𝖊𝖉, 𝕻𝖗𝖎𝖓𝖈𝖊 𝖔𝖋 𝕺𝖙𝖗𝖆𝖓𝖙𝖔, 𝖍𝖆𝖉 𝖔𝖓𝖊 𝖘𝖔𝖓 𝖆𝖓𝖉 𝖔𝖓𝖊 𝖉𝖆𝖚𝖌𝖍𝖙𝖊𝖗: 𝖙𝖍𝖊 𝖑𝖆𝖙𝖙𝖊𝖗, 𝖆 𝖒𝖔𝖘𝖙 𝖇𝖊𝖆𝖚𝖙𝖎𝖋𝖚𝖑 𝖛𝖎𝖗𝖌𝖎𝖓, 𝖆𝖌𝖊𝖉 𝖊𝖎𝖌𝖍𝖙𝖊𝖊𝖓, 𝖜𝖆𝖘 𝖈𝖆𝖑𝖑𝖊𝖉 𝕸𝖆𝖙𝖎𝖑𝖉𝖆. 𝕮𝖔𝖓𝖗𝖆𝖉, 𝖙𝖍𝖊 𝖘𝖔𝖓, 𝖜𝖆𝖘 𝖙𝖍𝖗𝖊𝖊 𝖞𝖊𝖆𝖗𝖘 𝖞𝖔𝖚𝖓𝖌𝖊𝖗, 𝖆 𝖍𝖔𝖒𝖊𝖑𝖞 𝖞𝖔𝖚𝖙𝖍, 𝖘𝖎𝖈𝖐𝖑𝖞, 𝖆𝖓𝖉 𝖔𝖋 𝖓𝖔 𝖕𝖗𝖔𝖒𝖎𝖘𝖎𝖓𝖌 𝖉𝖎𝖘𝖕𝖔𝖘𝖎𝖙𝖎𝖔𝖓; 𝖞𝖊𝖙 𝖍𝖊 𝖜𝖆𝖘 𝖙𝖍𝖊 𝖉𝖆𝖗𝖑𝖎𝖓𝖌 𝖔𝖋 𝖍𝖎𝖘 𝖋𝖆𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖗, 𝖜𝖍𝖔 𝖓𝖊𝖛𝖊𝖗 𝖘𝖍𝖔𝖜𝖊𝖉 𝖆𝖓𝖞 𝖘𝖞𝖒𝖕𝖙𝖔𝖒𝖘 𝖔𝖋 𝖆𝖋𝖋𝖊𝖈𝖙𝖎𝖔𝖓 𝖙𝖔 𝕸𝖆𝖙𝖎𝖑𝖉𝖆.1

Imagine reading an entire novel in that mess. The book itself, of course, is not printed that way. He's cheating to create a physical artifact that didn't really exist. And that's really interesting on its own. Gothic fiction, traditionally, does stuff like this all the time.

Frankenstein is one of the most famous examples. The novel is actually a collection of letters written by a man named Walton to his sister. In these letters, Walton describes Discovering a man out on the ice in the arctic, and that man is Victor Frankenstein. And as Walton sits and talks to Victor, Victor narrates his life story. So the entire story of Frankenstein's inside these letters, it's a frame narrative. Castle of Otranto is not that elaborate and the frame story isn't that interesting. But it's important to know that the very first gothic novel uses this technique.

The second preface is more literary. It admits that Walpole wrote the book. It was popular enough for a second printing, so he's taking the credit where it's due. People probably knew he was already. In fact, throughout this preface, Wolpole talks about Voltaire a few times. One of the moments is when he points out that Voltaire was clearly the author of the introductory essay in a book of his work, even though it was ascribed to the "editor" of the work. The footnote in my edition actually points out that Walpole turned out to be correct; it's since been demonstrated Voltaire definitely was the author of that essay. Walpole is sort of slyly referring back to his own "translation efforts" while engaging in the discourse over what is and isn't good literature.

Walpole was interested in drama. He was interested in theater. And so he conceives of gothic fiction as theatrical. His source is Shakespeare. He talks a lot about "romances ancient and modern" by which he means medieval romances like Arthurian tales, where wizards and knights traveled the countryside fighting dragons. And he says that these aren't "natural" but natural romances of his day sort of aren't that interesting.

He says that nature was getting her revenge for being excluded from romances for so long. So, his goal was to combine the two types, and he wants to do what is usually described in modern terms as putting psychologically realistic people into extraordinary, fantastical circumstances, and exploring the ways in which they react to the events around them.

If you read the book, you'll note that their reactions aren't very realistic either. But they're in line with both theatrical and literary ideas of natural writing from Walpole's time. And more to the point, they dwell on how they feel. They don't briefly mention that they're in a dangerous situation and then just go for it. They shiver in fear, they sweat in dread, they peer about in dark catacombs and shudder as they consider the sounds they're hearing. It is psychological, in the sense of "psychological horror," even if it isn't exactly the way we'd expect someone to write stuff now.

It's also important to notice that Walpole doesn't think he's inventing anything new even when he says that he's invented a new form of the romance. It's still a romance and he still cites Shakespeare and Voltaire. He sees this as a development of what was already there. And the reason that's important is that every bit of speculative fiction is essentially rooted in this novel. Every fantasy novel, every science fiction story, every horror movie, has somewhere in its dna Otranto.

And this novel is rooted in. The interplay of the fantastic and the natural. And if you think about speculative fiction very carefully, you will notice that there's always an interplay between the strange and the ordinary. If a novel or a movie did nothing but show you extraordinary things, like aliens you couldn't understand or kaleidoscopic dimensional transportation, you wouldn't be able to make anything out of it. There wouldn't be any ground to stand on. The best science fiction novels divorce you from your day-to-day existence. They're supposed to confuse you a little. The technical term for it is cognitive estrangement.

It eventually comes back around to helping you figure out what it all means, of course. It guide back. No science fiction novel is about the future. It's always about the present. No fantasy novel is about the past. It's always about the present.

The gothic novel is overtly set in the past. That's another thing about the traditional stuff: the gothic meant medieval. If you've ever wondered by ghost stories are so often set in old dusty mansions, it's because they always were, in a literary sense. The gothic in some sense is about grappling with the past, with the stuff we don't like to admit is back there. It's as though the past is a basement, and humanity has all this crap down there they don't like to think about (such as tyranny, torture, "superstition," so on, so forth). It's why the gothic is often read as "literature of anxiety" in literary criticism -- it's where a culture goes to worry about things.

I mentioned earlier that Walpole was particularly interested in theater. The novel is specifically dramatic. The notes to the Broadview edition point out how Walpole uses theatrical conventions, down to describing things as though they're on a stage. One thing to note in particular is the use of the servants. Walpole and his preface defend the use of the rustics. Which some critics had complained about at the time of the novel's first publication. He says that just like Shakespeare's rustics, the servants are "natural." There's a lot of classism happening here because he's effectively saying that poor servants are stupid. But they're natural and therefore they have a place in the novel. And that when they delay the plot because they can't speak well, they're making you anticipate it more which is actually a benefit. Walpole points out that if you're feeling impatient to get to a big reveal, you should realize that it means you're invested in what's happening.

He's playing with dramatic reveals with showing you what's in the wings and making you sit through half a scene of something else happening, even though it's a novel, The idea that a novel was overtly dramatic, was relatively new. Novels and theater weren't the same thing at all.

Chapter 1 Summary

There's actually a *lot* more in this chapter than I remembered. So.

- Can you hear those wedding bells?! Conrad and Isabella are getting hitched! Manfred is the local prince and Conrad is his son

- But wait, why is the groom delayed? Oh, an enormous knight's helmet, sable plumed, plummeted from the sky and crushed him to death, are you enjoying page 3?

- The bridegroom, Isabella, is, well, let's say she is sad a dude had to die but not exactly regretting the lack of marriage happening

- Manfred begins what we can only describe as losing his fucking mind. For REASONS he really really needs this, he needs his seed to get passed on here. He's got a daughter he hates and this one son, who is now as flat as that dog in Fish Called Wanda.

- Some peasant standing there gawping says this is just like the prophecy, you know, that prophecy everyone here in Bumfuck Italy knows about.

- Manfred immediately accuses the peasant of being a necromancer who cursed his son to death. All Manfred's noble friends try to talk him out of this, but Manfred has his servants trap the peasant under the helmet.

- Wouldn't that be a sensible place to end the chapter? Hell no, we're just getting started. Modern fiction's pacing wasn't invented until the 19th century fuck your rising action graph

- Hippolyta, who is Manfred's wife, is distraught. This makes sense. She is cloistered in her bedroom along with her daughter, Matilda, and Isabella, who has become like a second daughter to her.

- please read this phrase again, it will be important in a minute: Isabella has become like a daughter to this family.

- Manfred is storming around in his private chambers like one does, all gothically. He summons Isabella and meets her outside his room, in the castle's gallery. In this conversation he reiterates that he must have an heir and this whole son dying on his wedding day is actually great because that son sucked. And it's all Hippolyta's fault. Obviously, right?

- So Manfred is gonna marry her. Right the fuck now

- big yikes from team Isabella here. She runs off as soon as she's able

- why is she able? Oh, well, one of the portraits stepped out of its frame and walked the length of the gallery and into Manfred's chambers. That's all.

- Isabella makes it into the caves under the castle. Except there are doors and tombs and such in there? It's not really clear. I want to call it a catacomb, but ???

- She knows, somehow, that there's a secret door in a wall there, and that the tunnel it opens onto goes all the way to the local church. She wants to use it to escape and maybe even to live in, if Manfred won't stop pursuing her -- she'll just become a nun.

- She runs into the peasant (that's still his name, though I think I remember he's Theodore?), who's wandering around in the catacomb because the helmet broke some of the ground outside and he was able to slip through the hole and into this place. More on this encounter later.

- When they hear Manfred coming, they make to slip into the secret passage. Isabella makes it. Peasant waits too long and the door slams shut. He doesn't know how to make it work, so he's just sort of standing there like an idiot when Manfred and some servants come busting in.

- No, this still isn't the end of the chapter.

- Manfred asks what the peasant is doing. The peasant makes a big deal about how he doesn't have to answer. Then he answers. He's trying to buy Isabella time.

- Manfred wants to know what the door slamming sound was. Peasant says it was some door somewhere.

- Manfred asks again, and at that point Peasant decides to tell the truth and say he was the secret passage door closing. Manfred asks how he knew about it. Peasant says plenty of people do, c'mon, guy. Manfred asks how he opened it. Peasant raps on the door, doing absolutely nothing. The narrator says this is a move to warn Isabella to hustle.

- For a reason that goes unexplained, this impresses Manfred, who does not, at this time, know Isabella is down there.

- Then the "simple" servants interrupt. Fun times. This is drawn straight out of Shakespeare. They fumble their words and can't tell anyone anything. One's apparently drunk, or at least well known to usually be drunk while on duty. The other is the one who mostly speaks. At one point, he makes the same comical mistake that Dogberry makes in Much Ado, confusing "comprehend" and "apprehend."

- Finally, the story: searching for Isabella in the gallery, they saw a giant foot and ankle protruding into the study Manfred was just in. Manfred is at first dismissive but then remembers the gallery portrait and freaks out.

- Peasant offers to go look. Manfred says he must see for himself, but he takes Peasant with him.

- They run into Hippolyta, who's out looking for Manfred. She went into the gallery and Manfred's rooms and saw no apparition, though the narrator tells us she still worries something was there. Manfred feels the same.

- Everyone goes to bed. Peasant is sort of under house arrest now, but in a room and not under a helmet.

How is that one chapter? It's a lot.

Genre and innovation

OK, so the overall thing I want to say is a callback to this joke I made.

Modern fiction's pacing wasn't invented until the 19th century fuck your rising action graph

A significant number of the things we think fiction "must" do are conventions. Fiction doesn't have to do anything. It's not driving on a public road or building a bridge or applying to law school. There are no rules. There's nothing, and then there's something.

Before genre conventions harden -- and especially before consumer markets harden them -- writers had a kind of freedom it's nearly impossible for us to imagine nowadays.

Have you ever seen a musician say that they don't really have a genre, they don't believe in genre, it's limiting man? And you roll your eyes because they're inevitably doing fucking pop rock or dungeon synth or something really, really identifiable? The reason they're doing that is that genre is, at its core, a set of understood conventions that artists and audience members move within. They're not rules. They're a set of expectations.

Paul Kincaid has written, specifically in SF studies, that genres work through a series of "family resemblances" (he gets it from older philosophy). So not all SF has a rocket ship, but teleportation looks like a rocket ship because they're both impossible (in the 1930s let's say), and so they both sort of fulfill the same need for a technological novum (new thing -- it's a technical term in SF studies) that cognitively estranges the audience from the text.1

The point here regarding Otranto is that it literally invented the genre. It didn't exist yet, so there were no expectations. It's a kind of romance, so there will be some supernatural stuff, some attempts at marriages, and a kind of "wilderness." The gothic castle becomes the wilderness, basically. It's a strange place, full of horrible sights, dark corners, catacombs, poorly-lit rooms shuttered with arras, the works.

But while we can perceive all the things we recognize from Gothic fiction, none of it works in quite the way we expect. This is not because Walpole is a bad writer, but because we have expectations that he didn't have. Remember Twilight, and how the author bragged about how she had never read any vampire fiction before? And remember how, like it or not, it was always just sort of weird in a bad way, like if you pick up something in your kitchen and there's that veneer of grease because the sudsy water was too dirty when you washed it last night? And, like, it's working, and it's basically clean, but you want to put it down? That's the thing. A work that's in a genre but whose author doesn't know the genre expectations nowadays tends to make people uncomfortable. It just doesn't quite work somehow.

It's like insisting your genius is too good for learning how to do basic chords on a guitar. You gotta learn how the basics work first.

So for instance when Philip Roth said he was pleased that he'd invented a whole new genre for people to write, everyone was pissed off. Because what he'd written was a piece of alternate history fiction, and Philip K. Dick invented that with Man in the High Castle. But Roth doesn't know that, because he thinks he's too good to read science fiction, but he'll sure write it when he needs some money.

Unlike that, Walpole was setting up the expectations, but some of them lasted longer than others. So reading this novel can be a little topsy-turvy, a little weird, but in a much more pleasant way.

Short notes

This is long, I'm wrapping it up lol. When the Peasant and Isabella meet, they both freak out because they are in the dark, and neither of them are supposed to be there. An ever-present sense of terror is quintessential in the Gothic -- both are trespassing, both are under threat, both are in need of assistance, and both are nearly powerless without it. I'll talk about the differences between terror, horror, and dread some other time, but for now it's just important to know all three are different and all three are important to books like this one.

It's that time once again. In this installment, mostly people talk, but there is an attempt to wrongfully execute a guy.

CW for y'all: no actual incest happens, but the word comes up because the confused family relations, literal and figurative, make this the spectral sin Manfred is trying to commit, even though technically it's not actually incest.

Chapter 2 Summary

- Matilda, who you may remember as Manfred's daughter, is shut up in her room for the night with her servant Bianca. They're missing Isabella, who hasn't come back yet. They talk about the ghosts in the castle, Isabella, and whether Matilda should become a nun or get married. We are to understand this is a long-running debate.

- Bianca points out that Matilda would love whoever showed up at the castle if only they were pale with curly black hair. This is a joke: Matilda, it turns out, is obsessed with the portrait of Alfonso in the gallery. This will be important later.

- Peasant, whose name is Theodore, I was right, breaks into their conversation accidentally. He's basically at the window of the room he's been shut up in lamenting. They talk briefly, but when he asks about Isabella -- hoping to hear that she's safely escaped -- Matilda assumes he's just some skeevy dude up in Isabella's DMs and shuts the window.

- This is one of the most important moments in the plot, because there's a good amount of crosstalk that keeps fucking the characters over. If they'd had a slightly longer conversation, they would have known each other in the events to come. If this sounds like the way shit keeps getting worse in a Shakespeare play, you are correct.

- Meanwhile, Manfred is convinced that Theodore is Isabella's lover, and that they were a-trystin'. Father Jerome shows up while Manfred is Manfredding all over the place about this problem.

- Father Jerome runs the nearby abbey that Isabella has escaped to. He's come because he knows what happened and he wants to talk Manfred down. Jerome is a frequent visitor, because he works closely with Hippolyta on church matters and praying and such like.

- If you are noticing that this is mostly people talking and the summary isn't that funny, you are correct. All the action, so to speak, is at the end, and while all of this is important it's not all that interesting.

- So, with Jerome there, the church's representative in the area, Manfred takes the opportunity to get him alone and convince him to give Manfred a divorce.

- Jerome actually confronts him about Isabella first, and starts to have this conversation in front of Hippolyta. Manfred calms down because this would be Very Bad, and Hippolyta, seeing he's distressed, leaves of her own volition.

- This conversation is a big deal. It establishes that Manfred is not a pulp villain who does evil because he's evil. He doesn't love his wife but he respects her, and calls her a saint. This is another genre marker being made ab initio: the traditional gothic villain is never just a huge douchebag. They have feelings and can be touched by pity, love, and fear. They are driven by a hidden spring that forces them past these feelings. Think of Heathcliff.

- Jerome does calm Manfred down, mostly by stalling. Manfred's excuse is that he discovered that he and Hippolyta are related. That means he has been unknowingly engaging in incest. This is a lie. And in fact it's an irony, since everyone considers his relationship with Isabella to be that of a father. As father-in-law, he's basically her second dad. And so his apparent desire to get her pregnant is effectively incestual.

- Jerome says he'll think about this and write to Rome. This is bullshit. But it works, Manfred calms down and considers that this keeps Isabella nearby at the least. Jerome, though, starts to get high on his own supply (of bullshit, is the joke here), and so when Manfred asks if Isabella and Theodore were lovers, Jerome says there was some interest at least.

- This is also a lie. He thinks the jealousy will make Manfred desire Isabella less. Jerome doesn't know two things. One: Manfred doesn't desire Isabella so much as he needs her because, for Reasons, he's obsessed with continuing his bloodline, and so he needs male heirs. Two: Manfred asked Theodore if he was Isabella's lover and Theodore obviously said no.

- Oh, and the third thing Jerome doesn't know is that Theodore is imprisoned in the castle. So Manfred drags him down to the court yard to execute him.

- Before we can get to the big set piece, Matilda walks by with Bianca. She gets interested because Theodore looks exactly like the portrait of Alfonso and as much as she passed it off as a joke, she is in fact kind of obsessed with that portrait. Just like Bianca said, she sort of immediately gets the hots for Theodore.

- Then, of course, she hears that Manfred's about to kill the guy, and promptly faints. This briefy distracts Manfred who checks on her, and of course he rolls his eyes when he finds out she's just fainted. But since Bianca is hollering that her mistress is dead, and since Theodore only knew about one noblewoman in this castle, he concludes Manfred his Isabella back in his clutches. His concern re-convinces Manfred that they were lovers and to the courtyard they go.

- This is where the action happens. There's a lot of big talk, Theodore saying he is content to die because he has not sinned enough to go to hell, and Jerome is there to offer him his dying rites. Jerome does so, and keeps trying to convince Manfred to spare him. He feels -- somewhat correctly, lol -- that this is his fault.

- Plot twist time: Jerome finds a birthmark on Theodore's shoulder demonstrating that A: Theodore is Jerome's child and B: is therefore a noble. There's no explanation yet but Jerome assures Manfred that he was not a bastard (conceived, presumably, before Jerome received holy orders) and is the rightful count of Falconara.

- They start to get into what this means when trumpets blare on the walls and the helmet's sable plumes wave ominously in the air.

Evil Gothic

18th Century gothic is interesting because its evils are very human. The supernatural often appears in a secondary role. 19th century gothic, like Frankenstein, Dracula, and so on, feature the supernatural more centrally, though I've also used those two examples on purpose: at the beginning of the century we get the Creature, who is not innately evil and in fact performs evil acts as a form of revenge against the evil perpetuated on him by Victor, an unassuming nerd who nopes out of child support payments (so, a huge dick, but not a supervillain). However, at century's end we get the titular Dracula, a malevolent, supernatural force marauding through history.

This speaks to more than a genre development, but it is enmeshed with it. My point is basically that evil was imagined differently in the mid 1700s as it was in the late 1800s. Very (very very very) broadly speaking, we can say that the gothic fiction of the 18th century shows us a fascination with people in power ultimately becoming evil as a result of desire and the past's power over us. Manfred is obsessed with preserving his line because, as we'll see later in the novel, his family usurped the castle and the noble line from the "rightful" heirs. He knows this, and he knows that if he should ever fail to continue his line the entire place will fall down around his ears (figuratively, though, I mean, turns out also literally). He desires that continuation. He's also trapped into a situation: his child wasn't killed by a random accident but by Providence, by a supernatural force bending back towards justice. If it weren't Manfred it would be his dad or his son, this was going to happen.

By contrast, we get gothic villains in the 19th century who are simply evil because of Herbert Spencer. I'm not going to bore you to death by summarzing chapter one of my dissertation, but the very truncated tl;dr is that Darwin's theories of evolution sparked deep and intense existential angst in the Victorian mind, but Darwin didn't really write about humans much, and when he did he didn't say much about societies. It was Herbert Spencer who took Darwin's theories -- really, a bad misunderstanding of them -- and applied them to human societies.

When I say Herbert Spencer invented racism I do not mean people weren't racist before Spencer, they certainly were; he kind of shaped the final form of racism as we know it today, in all its pseudoscientific glory.

So the Victorians were freaking out basically because it turns out everything they hated was natural (not really). Violence, hatred, lust, these weren't -- or weren't only -- religious relics, but powerful "natural instincts" that evolved humans could overcome but "degenerates" were victims of.

Writers such as Lombroso wrote whole books about how criminals were born, and that they had to be removed from the gene pool (mmmm eugenics 🤮 ). Useful or not, Victorian penal theory actually aimed at reforming criminals by teaching them useful trades (that, somehow, totally coincidentally, were the trades that weren't very well compensated). Lombroso is one of the people responsible for the contemporary penal theory that prison is just for keeping people away from the general population, because obviously they will continue to Crime if allowed to (the eugenics got buried but it's obviously still present in the dna).

What does all this have to do with Castle of Otranto? Well, as most of the theorists on the gothic will tell you, gothic fiction tends to reflect the anxiety of its times. And since gothic fiction is a genre, bound up in its conventions, there are conventional means of expressing that anxiety.

Stop me if you've heard this one before: people get anxious about overpopulation, consumerism, and conformity and zombies get popular.

How about this one: people start to notice that bloodless aristocrats control their lives and prey on them and vampires get popular. Look closely at War of the Worlds. It's a vampire novel.

So the thing is, Otranto set these conventions. And the thing about traditional gothic is that it's always about the past in some way. It's often set in the past -- Walpole, in the 1700s, was at least four centuries removed from the setting of his novel. The past is important to gothic because that's where the bad things come from. Be it the supernatural comeuppance of family misdeeds or the curse of vampirism that creates a monster, the past is fucking frightening.

This marks the gothic as overtly European and post-enlightenment, mind you. And it's why good works that complicate that assumption slap so hard in today's gothic fiction.

But, basically, an important element of the genre of gothic fiction was set early, by Walpole, because "weird" fiction tends to come out of the cracks and show people stuff they don't really want to think about or look at.

Keep that in mind when we talk about the grotesque at some point in the future.

To bring this back around to Manfred, though: Manfred decides to do evil things. And to some degree, he knows they're evil things. He does them anyway, because, to borrow the cliche, he believes the ends justify the means.

Good old cliches

Walpole didn't invent the rest of these cliches, of course, but he inserted them directly into gothic fiction's veins. Long lost heirs, family curses, these were all part and parcel of the romance genre that Walpole is developing from.

Doubt

This was far more pronounced in chapter one, but it continues now: no one knows anything. This should come up again when we get to more focused talk on terror and so on, but it's important to notice that no one has any fucking clue of what's happening at any given moment. All of gothic fiction is in the dark, so to speak.

Quite a lot happens in this chapter as well. I wonder if we'll find, as we continue, that the chapters alternate like that? Maybe not! I dunno!

Chapter 3 summary

- Remember the trumpet blasts and the helmet plumes quivering? Manfred briefly feels his guts turn to water and begs the priest to intercede on his behalf.

- He grants Jerome the life of his son, and sets him free.

- Then a servant runs up to say that the trumpet blast was the announcement that a retinue of knights has shown up at the castle.

- Finding the events were mundane, Manfred immediately hardens up again, imprisons Theodore, and sends Jerome off to bring Isabella back, that being the only way he will release Theodore.

- The retinue is carrying, and please take a moment to dwell on this, an enormous sword. It is so large 100 men are needed to carry it, and they "faint under the weight of it."

- As this retinue nears the helmet, the sword bursts from their hands and lands on the ground nearby. No one can shift it again.

- The knights are representatives of Isabella's father, Frederic, who has come to claim his daughter and Otranto, which is his family's by right.

- Manfred is, of course, caught holding the bag. They tell him it's time to either give over the castle and its holdings or duel Frederic's representative.

- He stiffens up, but again as in the previous chapter, it's important to note in passing that he's not just an asshole. He accommodates the knights fairly -- at least at first -- and invites them to supper. After an awkward supper where he keeps trying to have civil conversation and they refuse to even take their armor off or lift their visors, he brings them to his study so they can converse.

- He feeds them the sob story about Hippolyta being his cousin (a lie), and they are sympathetic. He tells them his only son was just killed, on the day of his wedding (true), and he just wants to fuck off and give up everything (veracity unclear, but probably at this exact moment untrue).

- But wait! The whole reason he wanted Conrad to marry Isabella was that it would join Manfred's line to Frederic's, and -- deep breath here

- Manfred's ancestor was the squire of Frederic's ancestor Alfonso, who was the rightful holder of Otranto. Manfred's ancestor showed up from the crusades telling everyone Alfonso had died and given the holding over to him. Frederic is coming to claim his family property back. So Manfred was trying to get his family's claim to the holding legitimated, so his family would no longer be holding it wrongfully. This doesn't come up in this chapter, but he *is* aware of the prophecy (I think I remember this correctly) and he's trying to circumvent it.

- Yeah, the prophecy, from chapter one, remember that? It's been a while, and there's been *a lot*, so I don't blame you if you don't.

- While all this is happening, Jerome went back to the monastery, where, for reasons unclear, they think Hippolyta is dead. He keeps telling people that's not true, as he *just saw her*, but the damage is done. In even greater fear and grief, Isabella has fled the monastery. Jerome turns around and heads back to Otranto.

- So, amidst the meeting, Manfred is now offering to marry Isabella himself, not because he wants to, but because his duty compels him to do so, as his peasants need a ruler, and his only son is dead. And this way, they can avoid violence and bring together the two families. The knights aren't having it, but they haven't yet just told him to go fuck himself.

- This whole time, Manfred has been acting like Isabella is just in her room.

- So Jerome, remember, he was coming back? He forces his way into the meeting with some younger monks. He picks up what Manfred is laying down and shuts up, but the younger monks do not and immediately start talking about how Isabella has run away.

- The knights quite naturally leap up, yell at Manfred, and take off to find her. Manfred accompanies them, and orders his house servants and soldiers to find her -- but to fuck up the accommodations for the retinue so they can't help.

- OK, are you still with me? because this chapter is not over yet.

- Remember Matilda? Well she realizes the *entire household guard* is gone, because they're dumb (haha, classism), and so they didn't think about whether any guards should remain behind when Manfred said they should go out and search for Isabella.

- Matilda realizes too that this is the only chance she'll have to rescue Theodore.

- There's a tedious but significant scene where he refuses to go without her, and slowly realizes she is not the princess he saved the night before, but now he's super in love with her. She finally shoos him out the front gate. She's in love too, but he'll fucking die if he stays.

- He makes his way to the monastery. Jerome isn't there yet, so he decides to take a walk basically, but into the "haunted forest" with his sword and shield, because it's finally time to prove he's knight material. He comes across the haunted caves. The narrator makes sure we know Theodore assumes it's just bandits or something.

- Guess what? You'll never guess. No way.

- He finds Isabella. She's hiding in the caves. He promises to protect her.

- A knight appears, having been told by some farmers that a maiden passed into the caves. Theodore blocks the way. They fight and Theodore fucks his shit up for him.

- Remember that the knights refused to take off their helmets, even to eat? Yeah, this one is Isabella's father Frederic. He was trying to go incognito.

- They realize their error, Theodore brings Isabella, and they finally get him patched up and sent to Otranto, as the closest place to get help.

- Chapter end.

That's so much stuff. Holy shit. What I want to talk about this time is hesitation and how that feeds into the psychological factors. That will also prep us very well for the discussion on fear, horror, terror, and dread. Let me include a passage here, which I haven't done yet.

The tenderness Jerome had expressed for him concurred to confirm this reluctance; and he even persuaded himself that filial affection was the chief cause of his hovering between the castle and monastery.

Until Jerome should return at night, Theodore at length determined to repair to the forest that Matilda had pointed out to him. Arriving there, he sought the gloomiest shades, as best suited to the pleasing melancholy that reigned in his mind. In this mood he roved insensibly to the caves which had formerly served as a retreat to hermits, and were now reported round the country to be haunted by evil spirits. He recollected to have heard this tradition; and being of a brave and adventurous disposition, he willingly indulged his curiosity in exploring the secret recesses of this labyrinth. He had not penetrated far before he thought he heard the steps of some person who seemed to retreat before him.

Theodore, though firmly grounded in all our holy faith enjoins to be believed, had no apprehension that good men were abandoned without cause to the malice of the powers of darkness. He thought the place more likely to be infested by robbers than by those infernal agents who are reported to molest and bewilder travellers. He had long burned with impatience to approve his valour. Drawing his sabre, he marched sedately onwards, still directing his steps as the imperfect rustling sound before him led the way. The armour he wore was a like indication to the person who avoided him. Theodore, now convinced that he was not mistaken, redoubled his pace, and evidently gained on the person that fled, whose haste increasing, Theodore came up just as a woman fell breathless before him. He hasted to raise her, but her terror was so great that he apprehended she would faint in his arms. He used every gentle word to dispel her alarms, and assured her that far from injuring, he would defend her at the peril of his life. The Lady recovering her spirits from his courteous demeanour, and gazing on her protector, said -

"Sure, I have heard that voice before!"

"Not to my knowledge," replied Theodore; "unless, as I conjecture, thou art the Lady Isabella."

First, note that Theodore's thinking is described. This was actually somewhat rare for a lot of history, at least in western literature.

In fact, the case has been made that Hamlet is the first time that a work in the English language provided an interiority to the characters that was not immediately expressed. The soliliquy exists basically to make us aware of what characters are thinking, right? But Hamlet is engaged in a game of cat and mouse, his friends even working for the king to catch him out. The entire plot hinges on Hamlet hiding how he feels from others. There's one line that is very often cited in this topic:

But I have that within which passes show,

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.

(Hamlet I.ii.88-9)

The very idea that a character, particularly on a stage, might feel one thing and say another, without telling the audience what they were actually thinking, was revolutionary. Think of Iago, who carefully describes the way he lies to Othello. He doesn't tell Othello he's lying, of course, but he tells us. If you've ever studied Hamlet in a classroom you've probably been asked if you think Hamlet is crazy or not. We don't know. There's no way to definitively say yes or no.

All that is relevant because Walpole loved Shakespeare, and used his plays as the perfect model of literature. And here, in Otranto, we see characters described as thinking in a complex way. We're told, it's not left as a mystery, but the depth of a character's possible feelings has been enlarged. Theodore convinces himself it's filial piety that makes him stick around -- and not, as the narrator doesn't state in that paragraph, that he wants to see Matilda again.

Then, in the scene with Theodore and Isabella, it's somewhat comedic, but it really shows off the sort of fear and hesitation that marks out the Gothic. No one is sure of anything, so they hesitate. And hesitations fuck things up -- but there's no other way to go about things, right? You have to stop and think about things before you act -- or you end up killing some innocent guy who just wants to find his daughter.

This hesitant reaction to things -- so out of the ordinary that they stun the character, basically -- survives into contemporary gothic. If you've ever been annoyed that a character in a haunted house movie hesitates and doesn't immediately flee when the ghost appears, this is why. I distinctly remember sitting in an armchair rewatching Night of the Living Dead back in grad school and feeling as though an idea really did click, like I could hear it click, because the main character is so "useless" in that movie because she's Isabella, she's the classic gothic protagonist. This is how genre can help define the way characters behave. And remember, Walpole was pressing back against the way characters in chivalric romances behaved. He wanted to intervene in the genre, make the characters more realistic, but still have what he saw as the good stuff, ghosts and knights and duels and shit.

The gothic is basically about taking one's worldview and destabilizing it. The characters become increasingly uncertain about everything, because everything they had taken to be true is not -- there are ghosts, Jerome's son is alive.

This chapter is mostly talking, and so with a very small sample size of four chapters, my speculation from last time seems to be holding up, and we're alternating between action and dialogue chapters.

Chapter 4 Summary

- Frederic arrives safely at Otranto, and the surgeons care for him and declare him out of danger.

- Isabella and Theodore came too, despite how neither of them should really be anywhere *near* Manfred at this point.

- If you were wondering how there could be more novel when Isabella escaped Manfred's clutches in chapter *one*, this is why.

- There is just an amazingly awkward conversation set piece around Frederic's prone form, in his sick bed. Everyone's gathered around.

- Frederic tells his story. He was imprisoned, and while held had a dream, in which he was told to go to a certain wood and there he would learn something necessary to help his daughter. When he's ransomed, he rushes there.

- After a few days, he and his retainers come across a hermit on the verge of death. They aid him, and while he is dying and at peace with the fact, he thanks them for their care. He also says when he first entered these woods, decades before, he was vouchsafed a sign and a message that he should only divulge on his deathbed. Frederic's arrival signals that the message is for him.

- The hermit tells him to dig underneath a certain tree outside the cave. After the hermit dies and Frederic lays him to rest, he and his companions dig, unearthing the giant sword from last chapter. There's a message engraved on it:

Where'er a casque that suits this sword is found,

With perils is thy daughter compass'd round:

Alfonso's blood alone can save the maid,

And quiet a long restless prince's shade. - Theodore has no idea what this means, depsite being the one in chapter one to recite the local prophecy.

- Isabella yells at him for being rude to her father.

- Manfred turns to look at Theodore and freaks out. Theodore, now armed and in armor, looks exactly like the portrait of Alfonso. He has a strong reaction, and barely calms down when his wife reminds him of Theodore's existence.

First, a quick note on that reaction of Manfred's to Theodore. Manfred thinks he's seeing Alfonso's ghost, and freaks out. This is very clearly inspired by Macbeth's gruesome vision of Banquo, but oddly, the Broadview edition doesn't footnote that -- and it's odd because it footnotes every other instance that even looks like it could be a reference to Shakespeare. Apart from noting it for interest, and as yet further proof of Shakespeare's influence on the book, there's not much to say, but it was worth talking about.

- Riled up again, Manfred beefs with Theodore and Jerome *again*. But story time isn't over. Theodore tells his tale now.

- When he was five he and his mother were kidnapped by corsairs.

- Yeah, there are pirates in this book. In flashback at least. They don't do much.

- Enslaved, Theodore's mother dies in less than a year, but secrets away a document proving Theodore is the child of the line of Falconara. When the corsairs are taken by Christian sailors, years later, Theodore is set free and dropped off in Sicily, near his father's land. But the raiders had destroyed the mansion when they took Theodore and his mother, so Jerome had sold the land and entered the clergy in the interim.

- Theodore had traveled into this province seeking Jerome's monastery.

- Theodore is allowed by Manfred to stay with his father for the night, but is enjoined on his honor to return the next day. He agrees.

- Matilda and Isabella can't sleep; each has figured out that the other is in love with Theodore, and each believes Theodore to be in love with the other -- maybe. That hesitation comes into play again.

- They talk, which is at first sort of hilariously catty, but they're too nice and so they have what is called "a contest of amity" and each vows to give up their interest.

- In the midst of that, Hippolyta comes in and says she's suggested to Manfred that Frederic and Matilda be wed, thus healing the breach between the two families. This is of course Bad News for Matilda, who is in love with Theodore.

- Isabella finally admits that Manfred said he wanted a divorce and that he wanted to forcibly marry her.

- Hippolyta says she will consent to the divorce, admonishes Matilda for loving someone as poor as Theodore, and goes to see Jerome.

- Jerome is horrified to learn Theodore is in love with Matilda, and makes him come to Alfonso's tomb the folllowing morning (while Matilda and Isabella are talking), to explain why. Theodore naturally doesn't care, and whiles away the night with dreams of Matilda.

- Jerome begins to unfold something big, and in fact begins to overtly quote and mimic the language of Hamlet and the ghost of Hamlet. But he's got a head of steam and just sort of vaguely talks about how God is going to punish Manfred's family.

- It is *extremely obvious* there's another reveal coming, but Hippolyta comes in at that moment. She asks to speak to Jerome alone, and Theodore, not noticing the intense vibe his father was creating, takes the opportunity to nope out.

- Hippolyta tells Jerome what's been going on, and how she's even willing to go through with the divorce. Jerome hates all these ideas, but all he can really say, in his position, is that the divorce is immoral and the church will never approve and so on, so forth.

- Double meanwhile, Manfred pitches the double marriage plan to Frederic: Frederic marries Matilda and Manfred marries Isabella.

- Frederic *says yes*. He has two reasons. One, Matilda is pretty. Two, he's all fucked up now and could not win a duel against Manfred. He also comforts himself with the idea that Manfred and Isabella will never have a male heir, and thus his own bloodline will be restored to the principality.

- Manfred goes to the monastery to find Hippolyta, finds her talking to Jerome, and gets hollered at by the friar for his trouble.

- Once again, we're reminded that Manfred has impulses other than evil: he must take a moment to recover from the awe that is inspired in him when Jerome repudiates his plans and threatens him with excommunication. But he still rallies and tells the friar off in turn. He also announces Frederic has accepted his plan, takes Hippolyta away, and orders a servant to wait around in the church to see if anyone else from the castle enters.

- Oh also though, when Manfred said he and Isabella would be wed, the statue of Alphonso, over the tomb, bleeds from its nose. I find it very funny that it doesn't weep, it gets a nosebleed to indicate divine disapprobation.

As in chapter 2, a lot of the heavy lifting was done here, setting up the various relationships, furthering them along, and creating the necessary hooks for further reveals and twists.

Since it's mostly talk, I struggle a bit to conceive of what to talk about. The topics I know I want to get to eventually are the grotesque, and the varieties of fear. One that suggests itself is the role of the religious personage in the gothic, but I have idle dreams of continuing this series, and it would make much more sense to talk about that when I re-read The Monk.

But what is appropriate for this chapter I think is the idea of foreignness.

The gothic was, effectively, an English genre. That's important because these novels were, for a long time, never set in England. They're often, in fact, set in Italy.

Otranto is set in Italy. So is Udolpho, and I don't think The Italian is just about one Italian guy, but I might be wrong, it's been a long time.

The Monk is set in Spain. Vathek is set in the caliphate. The thing to note here is that the gothic was originally a genre where, explicitly, bad things happened in other countries.

England was soundly Protestant, so all the gothic stories are about Catholics. England was reforming and moving into the future, so all these stories were set in the past. This is not as simple as saying that English authors conformed to, or utilized, their society's xenophobia, but that is part of what's happening.

But remember that the gothic destabilizes things. It undermines our sense of the normal, of the everyday. It's why the gothic became a place one finds queer fiction, and where we still often see it: the gothic is about confusing and blurring lines that everyday people think are clearly demarcated, and often about showing that the lines don't exist at all.

Here's an early elevator pitch for a way to read Otranto: a prince can do bad shit in his demesne and short of God intervening there is fuck all you can do about it. We want to think justice will save us, because we tend to think justice is a thing, a person.

Now, look, I'm an animist, so I do think there is a thing that's like that, but it's not the same as the human justice, the thing where you have to pay back your loans and you tacitly agree not to murder people.

The reason I bring that up in the same chapter that I bring up the gothic's use of the foreign is that everything that the gothic gives you that's revolting is also what we're drawn to.

Think of the line above, where Walpole archly says the two maidens have a "content of amity," and then think of how cool Manfred is, sweeping around everywhere, shouting at priests.

Byron wrote an excellent poem titled "Manfred." He didn't write any titled "Theodore." The gothic is where we get the best villains, right? Dracula, Mister Hyde, so on, so forth. Even as we know they're bad, and we deplore their actions, we are drawn to them by the force of the narrative and its transgressive nature.

Gothic fiction was not safe. Women were warned not to read it. Poets wrote about the cold sweats they got when they read it. And the "foreign" aspect of the narratives add to it. They are no longer only the countries that England believes itself to be better than -- they're also the exotic, startling places where cool shit happens.

And fiction is place, isn't it? We "go" there.

This is it, the big ending and all the reveals! I said recently that I intended to do this in two parts, but I think I'm going to try for one. I write this all unknowing, let's see what happens.

chapter 4 summary

- Manfred is convinced that Isabella and Theodore are trysting in secret. He goes to Frederic and puts his case to him again. Frederic, previously agreeing to the double marriage, is having second thoughts.

- But look apparently Matilda is mad hot, so he says yes again.

- Enter, as we might write in a script, the domestics. She comes in screaming and yelling. Once they dig through Walpole's idea of what poor people speak like (disconnected ranting basically), what's happened is that a giant hand, to match the previous giant foot, has appeared, and Bianca is leaving.

- Manfred of course poo poos this, but Frederic, believing her behavior to be genuine and not to be second hand, tells Manfred he will never marry Isabella: Manfred's under the curse of heaven.

- However, there's time for one more fucking weird thing before the novel ends: Frederic still really has the hots for Matilda, so he's sort of reconsidering his reconsideration. He seeks Hippolyta, because he wants to assure himself that Manfred's divorce is actually going to happen. He enters her chambers, and from there her private devotional room.

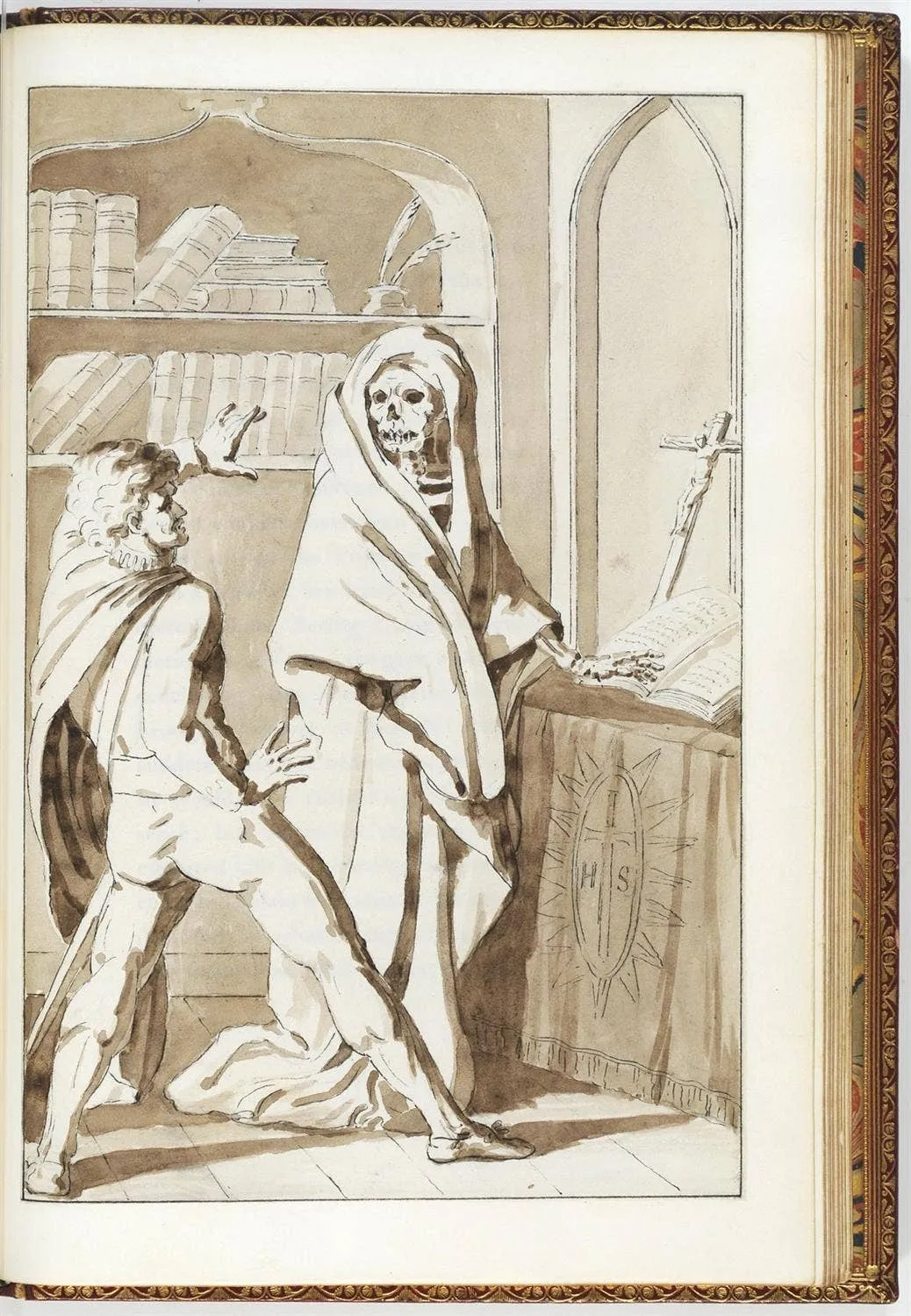

- Now this is the metal shit, just real sicko gothic amazement: Frederic sees a figure knelt in prayer. It rises and removes its hood and it's a fucking skeleton -- and better yet, it's the ghost of the hermit who led Frederic to find Isabella in the first place.

I want this in a block, this is some cool shit. Here's the scene.

“Hippolita!” replied a hollow voice; “camest thou to this castle to seek Hippolita?” and then the figure, turning slowly round, discovered to Frederic the fleshless jaws and empty sockets of a skeleton, wrapt in a hermit’s cowl.

“Angels of grace protect me!” cried Frederic, recoiling.

“Deserve their protection!” said the Spectre. Frederic, falling on his knees, adjured the phantom to take pity on him.

“Dost thou not remember me?” said the apparition. “Remember the wood of Joppa!”

“Art thou that holy hermit?” cried Frederic, trembling. “Can I do aught for thy eternal peace?”

“Wast thou delivered from bondage,” said the spectre, “to pursue carnal delights? Hast thou forgotten the buried sabre, and the behest of Heaven engraven on it?”

“I have not, I have not,” said Frederic; “but say, blest spirit, what is thy errand to me? What remains to be done?”

“To forget Matilda!” said the apparition; and vanished.

That, as they say, is that.

Chapter 5 summary

- Pissed off at the world, Manfred does what any self-respecting dude would do: gets kinda toasted. Liquored up, he hits on Isabella at supper, and she shuts her door in his face.

- Now assuming she's rushing off to meet Theodore, he meets the servant who was spying in the church. He affirms Theodore entered, with a lady, but it was not clear *who*.

- Here, I might take a moment to point out, is the uncertainty rearing its head again.

- Manfred is certain Isabella has run off, and so he rushes to the church, sees Theodore talking to a woman, and *stabs the shit out of her*. Like, in the chest, this lady is dead now.

- Except it'll be 8 pages or so before she dies, we have to get the rest of the novel in.

- Also I just bet you see what's coming here: it was Matilda. Manfred has killed his daughter, who was coming to the church to pray and met Theodore by chance.

- They rush Matilda back to the castle. Manfred is finally broken, and repents all his actions. Hippolyta sits by her daughter's death bed. Theodore weeps and kisses her and tries to get Jerome to marry them right now, like, *right now right now*.

- Frederic, being That Guy, takes a moment from grieving the death of Matilda to say Theodore is being a little entitled shit -- not for any reason you would approve of, but because *he's a landless bastard*.

- And here comes the rest of that story. Theodore blurts out that he's the rightful prince of Otranto. Jerome fills in the rest. When Alfonso went to the crusades, he was stuck in port for several months near Sicily, and married a young peasant woman there. Naturally she was pregnant. Alfonso's intention was to bring her home with him upon the return leg of his journey. But he died. His wife, Victoria, had her child, a daughter. That daughter married Jerome.

- And how did he die? Oh yeah, Manfred's grandfather poisoned him. Ricardo was his name, and the entire will was a forgery. Ricardo, on his way back home is beset by storms, because he's a filthy poisoning usurper. But he swears to build two churches when he gets back, so Heaven says, yeah, cool, sounds good.[^1] But, when there's no male heir, the whole kit and caboodle is going back to Alfonso's line.

Here's another point where I want to put the text in front of you. This is it, the big climax. When everyone goes out into the courtyard, hearing shit falling down around their ears, Manfred cries out that Matilda is dead and a big old giant pops out of the castle, ruining it in the process. He grabs his sword and helmet and flies into Heaven.

Yes. Hell yeah.

A clap of thunder at that instant shook the castle to its foundations; the earth rocked, and the clank of more than mortal armour was heard behind. Frederic and Jerome thought the last day was at hand. The latter, forcing Theodore along with them, rushed into the court. The moment Theodore appeared, the walls of the castle behind Manfred were thrown down with a mighty force, and the form of Alfonso, dilated to an immense magnitude, appeared in the centre of the ruins.

“Behold in Theodore the true heir of Alfonso!” said the vision: And having pronounced those words, accompanied by a clap of thunder, it ascended solemnly towards heaven, where the clouds parting asunder, the form of St. Nicholas was seen, and receiving Alfonso’s shade, they were soon wrapt from mortal eyes in a blaze of glory.

The beholders fell prostrate on their faces, acknowledging the divine will.

last bit of plot summary

- There's a bit left. Actually the explanations above happen after the giant appears, But I saved him until nearly last. Manfred, after explaining his grandfather's crime, laments, agrees to give up any claim he has to the demesne.

- Manfred and Hippolyta cloister themselves away in their respective churches.

- Frederic offers Isabella to Theodore, who's too depressed to say yes. But she stays on, and they become friends over *how sad they are*, and then they get married.

- Seriously. This is the final sentence of the novel:

But Theodore’s grief was too fresh to admit the thought of another love; and it was not until after frequent discourses with Isabella of his dear Matilda, that he was persuaded he could know no happiness but in the society of one with whom he could for ever indulge the melancholy that had taken possession of his soul.

Loose Ends

Does that ending feel satisfying? I can't remember which book I read it in, but at one point in grad school I read that some critics have pointed out that the unsatisfying ending of Otranto may be to leave the reader unsettled. It both gives you the moralizing ending that it's "supposed to," where the sort-of incestuous villain gets his just desserts, and at the same time it refuses to let you get satisfaction from it because God did it, everyone kinda sucks, and really wasn't the fun part watching Manfred be an evil shit?

I think this is a good reading, but it bears complication: Walpole thought of this as a kind of play, not really a novel; anyway, the strictures of the novel were not as binding then as now. And plays, if you've seen or read anything from Shakespeare to Racine, do not have to give a single fuck about whether you're happy at the end. Things just fucking happen up on that stage, and the immediacy of the performance will make things work that might not appear to on paper.

With that said, it's also worth noting that the five chapters of the novel probably correspond to the typical five act play structure.

Big Reveals

I've teased on several occasions that I would talk about the grotesque and the kinds of gothic fear. But to my surprise, this novel doesn't really provide any good ways into those topics. Things happen to quickly for dread. The dead and dying are beauteous with their hopes for Heaven, and don't disgust onlookers even as they remind them of death. No nuns are getting trampled to death here. 2

Understand right now that I'm not promising anything in a hurry, but I already bought a better edition of the second gothic novel, Vathek. So I'll probably be back here at some point in the future, doing this again. So please look forward to those topics in the future.

If anyone wants me to read Radcliffe in the future, give me money. Like, seriously, I may start some kind of campaign on Ko-Fi and Patreon.

At any rate, I titled this section Big Reveals.

Here's a comment from one of the footnotes:

It might be said that the Gothic novel is a primitive detective story in which God or fate is the detective. (Bleiler, qtd in Otranto, Frank, ed. p. 162.)

This is both a good point and a bad one. It's a good point because it makes us think about detective fiction. It's bad because all detective fiction is gothic fiction.

Again, referring to that kind of "genetic code of genre" metaphor we used a while back, detective fiction is a descendant of the gothic.

The first detective story, in the western world at least, is The Memoirs of Vidocq. Non-fiction, at least at first, they were actual memoirs, of an actual thief that the French authorities released from jail once he helped them catch an even more skilled thief. He became a kind of consultant for the police.

This presumably sounds familiar to you.

The series was quite long, and eventually became fiction, but still with that veneer of non-fiction on it.

The first overtly fictional detective story, though, is by Edgar Allan Poe. He invented the genre, basically, with "Murders in the Rue Morgue." And if you haven't read that, here's the thing: the narrator is friends with the detective, Dupin, and they both live alone and take long walks at night, while sleeping in the day, in their rooms where they've covered over all the windows so they can live in perpetual gloom. Skulls and other macabre decorations litter the rooms. These fuckers are goth in two senses of the word (gothic fictional and also club kids; they are not, in fact, Visigoths).

The gothic is always about a mystery, right? There's a thing in the darkness, and you don't want to see it, but you have to see it. People creep around in graveyards and in catacombs, finding clues that add up to horrifying discoveries.

It's just that the detective uses the power of rationality -- ratiocination in Poe's words -- to reorder the world, to make it make sense again.

Thanks for coming!

I'm leaving it there because we've already run long enough and you probably have something else to do.

An artist did an illustrated edition of Otranto and honestly the images kind of kick ass.

Walpole, The Mysterious Mother, and Fandom

"What the fuck" you might say. What the fuck indeed.

I'm nearing the end of the volume of Walpole from which my Otranto series came. It also includes The Mysterious Mother, Walpole's closet drama about an incestuous mother's lifelong ardent penitence and the eventual tragedy that results from an evil monk manipulating events. That's all I'm going to say about the incest, except to point out that the play's sources are clearly works such as Oedipus Rex, Phedre, and so on.

Walpole knew the people of his time and country wouldn't accept a production, and so he tamped down his desire to see it on stage and printed a few copies for friends. Naturally, some of those copies escaped into the wild. To prevent pirate editions, Walpole gave in and permitted an official printing. He was basically right about the reaction, though there were far more favorable reviews than he had expected.

Recorded in the diary of Fanny Burney is a strong negative reaction. She was a novelist and a lady-in-waiting to Queen Charlotte, and borrowed the queen's copy. Burney knew Walpole personally, I should point out; they were friends, and he had taken her on a tour of his "gothic villa," Strawberry Hill.

Here's a selection from her reaction:

Dreadful was the whole! truly dreadful! a story of so much horror, from atrocious and voluntary guilt, never did I hear!.... For myself, I felt a sort of indignant aversion rise fast and warm in my mind, against the wilful author of a story so horrible: all of the entertainment and pleasure I had received from Mr. Walpole seemed extinguished by this lecture, which almost made me regard him as the patron of the vices he had been pleased to record."1

It's worth reading this response carefully: from previously recorded delight at the writing, and from her past experience of happiness and friendship with Walpole, Burney pivots to a kind of moral outrage. The play doesn't depict the "vices," to be clear; it also clearly repudiates them, though the engine of the play, to borrow his phrasing from the preface to Otranto, is to simultaneously build up the past sin of the Countess while engendering feelings of pity for her in the audience. This pity in no way obviates the "crime" she has committed.

From that pivot Burney goes on to say that she felt as though Walpole -- with absolutely no concrete reason whatsoever -- was "the patron of the vices he had been pleased to record." She felt as though he approved of the crime. The mere fact that he had been "pleased to record" it -- even in passing, and not directly depicted on stage -- meant that he must in some way find them acceptable.

You may find this familiar if you're engaged in any fandom discourse, as it's a perennial problem nowadays. It's very common for fanfic authors -- and increasingly, even "traditional" authors -- to be pilloried online for being bad people just for writing about bad things. And mind you, this has nothing to do with something like content warnings or revenge porn or something like that. It's about the ability of art to take on any topic, and for good art to help readers think about it.

If I have a thesis here, it's really this: this problem is older than you think. Indeed, the gothic is an excellent analogue for fandom within genre and fandom studies. Both were considered transgressive, weird, feminine, maudlin, schlocky, and lesser than other forms of art. They have reputations for being full of tropes, of using mechanical plots to pilot meager characters towards bombastic climaxes... the comparisons can go on.